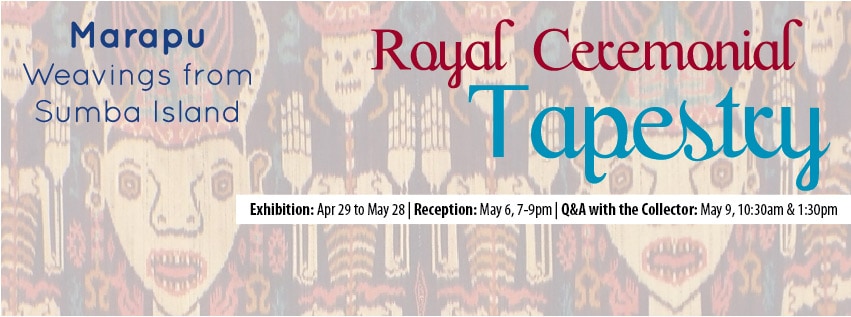

Submitted by: Geoffery Bendel, Collector of Sumbanese Textiles

The Island of Sumba

The Island of Sumba

Sumba is an island in eastern Indonesia. It is one of the Lesser Sunda Islands, in the province of East Nusa Tenggara. Sumba has an area of 11,153 square kilometers (4,306 square miles) and a population of just over 600,000 people. It is nestled in the Indian ocean about 600 kilometers east of Bali and west of Timor island; an undulating, rugged green savannah with low limestone hills, knitted together by corn, cassava and rice fields in the interior, with spectacular windswept beaches along its coastline. The vistas in Sumba look unlike any other place in Indonesia; it has been observed that the topography looks more like Africa or parts of Australia than the volcanic islands that surround it. Geology has determined that Sumba is actually a piece of the Australian land mass that broke off and migrated through tectonic shifts over the last 120 million years.

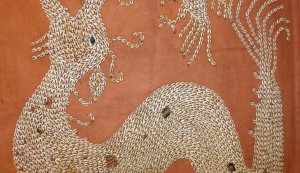

“Pikat (Hornet) Cloth” by Ibu Sri Bunga

The people of Sumba are among the last living examples of a vanishing megalithic culture, notable for its ancestor worship, hierarchical society and fierce sense of chivalry. Throughout the countryside, hilltop villages with high peak thatched clan houses are clustered around megalithic ancestral tombs. The Sumbanese are a horse riding people, famed over centuries for their sturdy, spirited horses and mammoth water buffalo. For at least two thousand years the Chinese, and subsequently Portuguese, Arab, Indian and Dutch traders, have been visiting Sumba’s shores to trade for sandalwood, spices, horses, and more… Headhunting was part of inter-village warfare until as late as the 1940s; however, widespread conversion to Christianity and modernization has rendered that practice a footnote to history.

Christianity is the dominant religion but an estimated 30% of the indigenous population adheres to the animist practice called Marapu. Despite the transition to Christianity, Marapu still exerts its hold through symbolic and ceremonial rites. Many Christians on the island combine their faith with animist practices. Marapu religion believes in temporary life on earth and an eternal life in the world of spirits in Marapu heaven (Prai Marapu). Marapu teaches that universal life must be balanced and only then can happiness be achieved. This balance is symbolized by the Great Mother (Ina Kalada) and the Great Father (Ama Kalada) who live in the universe and take the forms of the moon and the sun. They are husband and wife who gave birth to the first ancestors of the Sumbanese.

As in many animist religions, Marapu practitioners believe in a myriad of nature and animal spirits, and hold that spirit is dynamic and immutable in all things seen and unseen, present in important places such as the ancestral tombs and stone alters that give Sumba its uncanny megalithic atmosphere, and also in trees, rocks, and water.

Sumba is a dynamic place where old world meets new, where ancient practices and landmarks co-exist alongside recently made roads, motorcycles, and other accouterments of modernity. Tradition and continuity is conveyed in the island’s amazing historic artistic traditions. They include stone and wood carving, basket weaving, objets d’art, and the famed Sumba tapestry, Ikat.

Introduction to Sumba Textiles

Detail of hand stitching “Lau Hada with Naga” by Unknown artist

Centuries of tradition have enabled the people of Sumba to refine the art of tie-dyeing skeins of thread into one of the most sophisticated textile processes in the world, known as “Ikat.” Ikat is the Malay/Indonesian term meaning to-tie. This millennia old-form of textile production has been practiced as an art form by cultures in South and Central America, Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. It is widely recognized that Indonesia’s finest woven patterned and resist dyed fabrics stand at the very pinnacle of achievement in the textile arts, and that Indonesian ikat production reached its apogee in Nusa Tenggara, and most notably in Eastern Sumba, in the mid-late 20th century.

Sumbanese textiles have been a source of wonder for travelers and collectors since the Dutch conquest of Indonesia brought them to Western notice at the end of the 19th century, and are found in major museums around the world, as well as in private collections. They stand as a testament to the sophisticated worldview of a frequently misunderstood culture, as well as a genealogical and historical record of a tradition that is otherwise preserved primarily through storytelling. Design elements borrowed from Sumba Ikat can be found in diverse places including interior design, clothing, wallpaper, watermarks, and marble tiles, and even adorn sporting goods such as surfboards. It has also been noted that surrealist and modern European artists were influenced through encountering Sumbanese ikat in museums and exhibition catalogs.

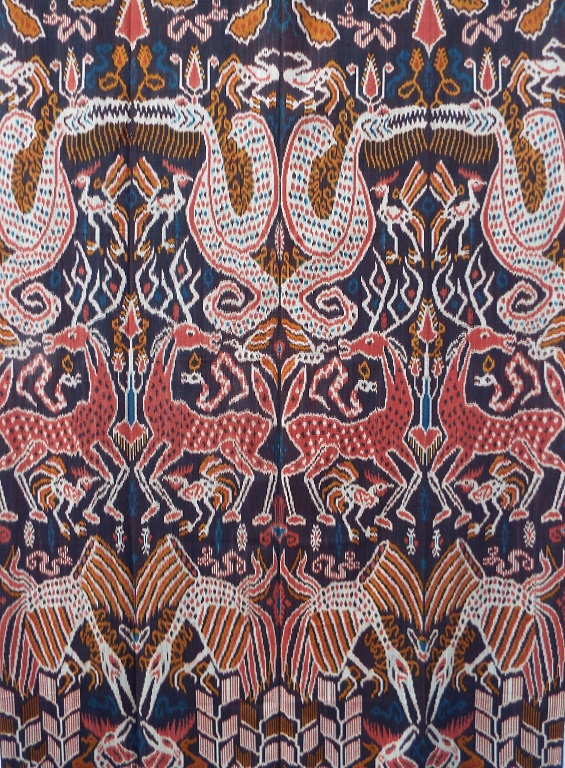

“Great Mother (Ina Kalada) and the Great Father (Ama Kalada)” by Ibu Yohana

The motifs embedded in the richly dyed threads converge to form symbols that represent the village of birth, patriarchal ancestry, social/marital status, and on occasion designate royal lineage. The images on the textiles reflect the island’s Marapu animist faith. Distinctively Sumbanese motifs often include anthropomorphic and mythical creatures, as well the skull tree, a legacy of the days of head-hunting warfare between villages. Horses, water-buffalo and other revered animals signify wealth and status. Often times lobsters, crabs, or creatures that shed their skin are displayed as they symbolize regeneration and renewal. Plants and flowers are often shown in abstraction, and have multiple symbolic meanings. Many designs are reserved under strict code for use only in royal textiles; these images often include dragons, lions, royal crests, as well as crocodiles and other aquatic animals. Sumba cloth also often features human figures, in a myriad of forms, sometimes in symbolic battle, others in serene village life. Whereas the forms and symbols are many fold, they all are totemic, and weave a complex social narrative.

The personal wealth of a Sumbanese person would historically be determined not only by the number of animals owned, but also by the number and (of utmost importance) the quality of textiles in their possession. These pieces are revered for their perceived totemic powers, and convey both sacred importance and the owner’s social status. The Sumbanese believe a person is able to acquire the spiritual powers and qualities of certain creatures when textiles displaying such motifs are worn. Textiles have been integral in ritual exchange for dowries and peacekeeping ceremonies, for use in fertility rites, and for marking various seasons and stages of success in life. Textiles are used both as clothing and as a currency of traditional ritual exchange. A full size hand spun Ikat of the highest caliber can take over two years to complete and the value can be worth more than a water buffalo or many horses. They are given at birth, they are central articles of the dowry upon marriage, and notably they are essential upon burial. Upon death, Ikat cloths are interred with the deceased, their function shifting from ritual clothing in life to a protective shroud in the journey to the afterlife, offering protection to the deceased on the journey to the Marapu, “land of the ancestors.”

Hingi Maramba, Royal Cloths

“Rusa (Deer) cloth” by Ibu Hedi

Textiles directly associated with the king or nobility are often longer and sometimes wider than the average mantle and are distinguished by their complex composition, often featuring privileged designs that can only be used by royalty, deeply saturated colors, and additional finishing touches like supplementary warp finishes on the ends of the cloth. The cloths made for the royal families take tremendous amounts of time and labour to produce, they are the greatest examples of this art form. Typically, these royal cloths never reach the international market, as they are forbidden to be sold to strangers, and are strictly used for Maramba (aristocratic) ceremonial purposes.

The majority of the textiles in this exhibition are Hingi Maramba, (royal cloths). I have been fortunate enough to live in Sumba with these amazing people for multiple extended periods of time since the late 1980s, and have been able to collect these pieces due to my extensive time living on the island and through decades-long, lasting friendships with the royal clans and local people alike. Because of my unique status as a friend/advocate of the local population, I have been allowed to build this private collection that has been described by the curator at the Indonesian textile museum in Jakarta as one of the world’s largest and most important private collections of Sumbanese textiles and artifacts.

The majority of these pieces, at this exhibition, are vintage or antique and have been hermetically sealed and in storage since the 1990’s. They form the basis of my private collection. The exception being four pieces of textile which I commissioned in early 2012 and were completed in late 2014, these pieces were created by the best of the last remaining ikat artists on the island, and are the genesis of a new weaving cooperative.

It is my distinct pleasure to exhibit this collection in Saskatoon, the city where I was born. It is my belief that people come to understand and appreciate each other through art, whether it is our immediate neighbors or an ancient indigenous culture living across the planet, and it is my hope that this exhibition will be received with the spirit of common humanity and sense of wonder at the natural world.

Thank you, for your interest.

– Geoffrey Bendel