Blog Article | Curated by Lana Wilson | Commentary by Sandra Ledingham

|

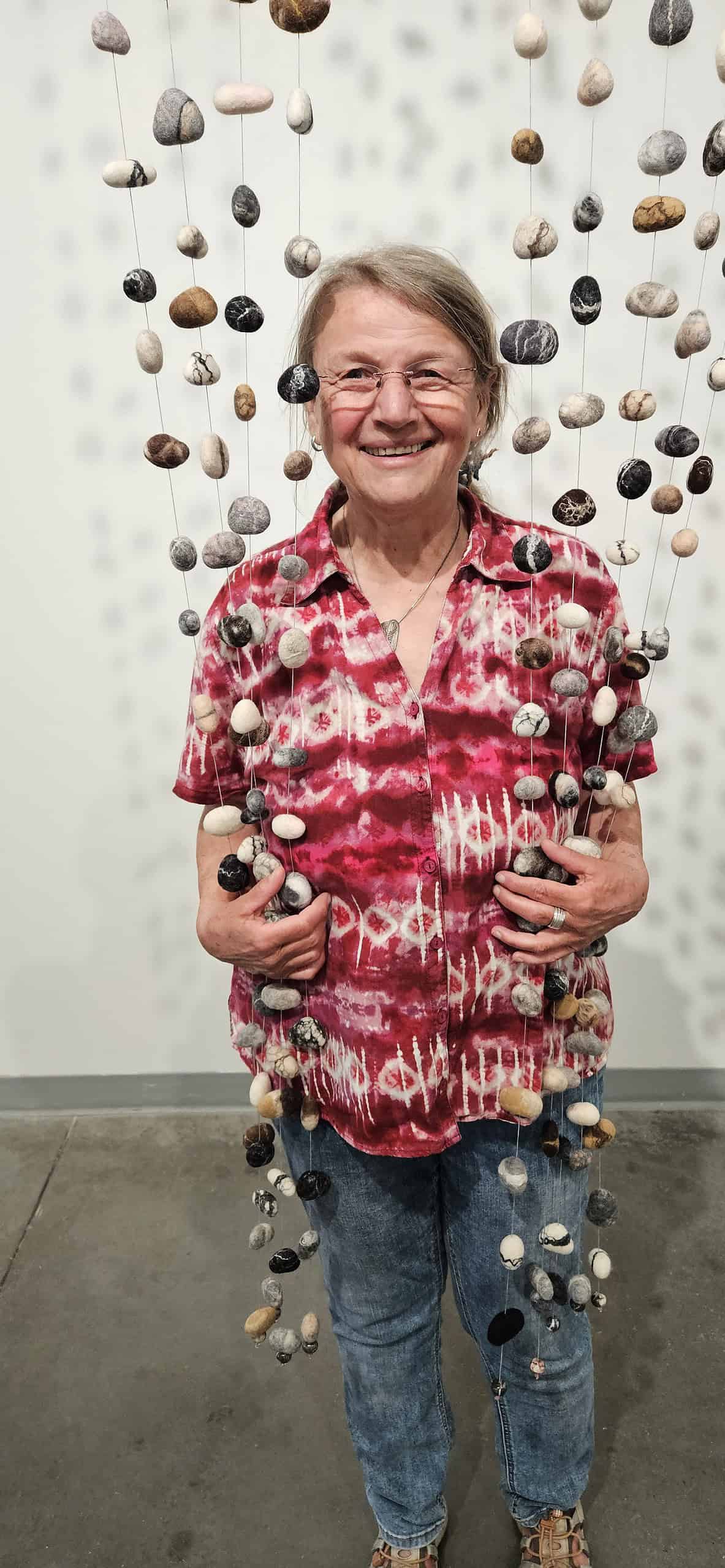

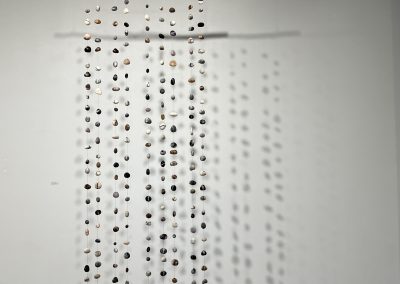

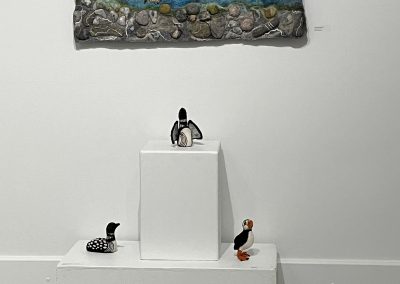

The solo show of fabric artist Heike Fink showed at The Mann Gallery in Prince Albert, Saskatchewan, from April 16 to July 2, 2024. It was Heike’s first solo exhibition in Saskatchewan, but the work was recently also shown in Germany at Felto — Filzwelt Soltau Museum, where she completed a residency and attended Filz-Kolleg, an annual felting conference(1). Heike came to Canada from Germany in 1994 as an activist, to look at how uranium mining affected Indigenous people living in Northern Saskatchewan. Two German companies were involved in establishing uranium mines in the North. “We were naively hoping to prevent some of their activities — but of course not!” Coming back to Saskatchewan’s North every summer from 1994 – 2004, two of their group established a small ecotourism company called ‘Northern Escapes’ to bring Germans to Northern Saskatchewan in an attempt to provide alternative jobs to uranium mining. “Lots of fun, but a financial disaster.” Immigrating officially in 2005, Heike bought a house in Prud’homme, and continued to work part time in Wollaston Lake. This allowed her to continue developing her felting practice, which she started in Germany in 2004. After viewing the show I met with Heike to discuss her work. Her artist statement speaks to her passion for ecology and the environment: “My art explores the relationship and balance between land, wildlife and humans, and the loss of wild space and — wildlife — pressing questions of our epoch.” The exhibition is vast and encompasses many concepts and styles. Central to the show is the very large, interactive floor-installation of 3,000 felted river rocks. Viewers are invited to mingle amongst the stones and interact with them; build a cairn, contemplate nature, lay down, reconstruct and deconstruct new assemblages. “Bedrock and rocks are the basis of all land; they embody a country’s history, and they are a deep connector to the ancient stories of the land and its peoples from First Nations to Métis to Settlers. Rocks represent flow and connection and I believe the embedded history in a rock is one of the reasons why people connect so deeply with rocks, be they real or felted.” These objects also read beautifully in a formal manner as textured spheres. Asked about her work as a Program Guide at Remai Modern in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, I was curious whether this exposure informed her thoughts and concepts regarding art-making. Her response: “I see my forms in a more abstracted way.” The show includes many approaches: figurative, abstraction, political commentary, installation, whimsey. There are many small, static, felted animals ranging from otters to racoons to bison to birds, as well as figurative works of celebrities: Leonard Cohen and Joe Fafard. This show displays technical rigor! Heike situates her work as fibre art, expressing her desire to present the small felted animals as sculptures. We discussed The Bauhaus school in Germany and whether their history of a strong fibre arts department had informed her practice. She felt it was currently not a conscious part of her making. The small pieces are arranged in vignettes (for example, otters frolicking in water), presented on white gallery pedestals. This begs the question of what makes a sculpture, or a toy, or art, or craft. I once came across a quote from curator Richard Jacobs, discussing the idea put forward by Gestalt theory and designers affiliated with the Bauhaus, that “an object is the sum-total of the qualities embedded within the work.”(2) For artists engaging with craft, this presents a challenge, as the “material-arts” carry with them much baggage and connotation: the material itself, the history of its usage, the technology used to make it, cultural references, and the gender of makers. Whether we as makers want it or not, for the viewer these associations resonate, mostly subliminally. In the case of wool, it is traditionally used for making clothing, hats, toys, blankets, rugs, boot liners, etc. The material itself speaks loudly as a soft, cuddly, warm, nostalgic and tactile material; and what gender is typically associated with the makers? Audiences are often surprised when they learn that fibre-art objects are made by a man. So how then does an artist have their material read as art, regardless of gender, and what does that look like anyway? An answer to this question can be found when artists experiment with new modes of making, and blur boundary lines, mess with the expected, and apply new technologies to familiar materials. Heike’s work aligns with an approach called “Craftivism” recently documented by Anthea Black and Nicole Burisch(3), due to her formative work in Northern Saskatchewan and her values. Heike’s artist statement focuses on her interest in endangered species, loss of habitat, ecology and land use, and these values are tools informing her making. We discussed the need for a curatorial role, editing, grouping of works and streamlining her intent to produce a strong message. I noted one title card with a Musk Ox, wondering if there were more endangered species in the exhibition? Grouping these together with a statement would have produced a greater impact for Heike’s intent. We discussed how many of the animals in the exhibit seem happy, and I inquired whether, for example, an otter being caught in a trap would direct viewers to more inquiry? In an excerpt from the Artist Statement, we read, “The animal sculptures stand as a symbol of the vulnerability of the land and its inhabitants. Surviving in disturbed habitats and showing their resilience, animals become a constant reminder for we humans to execute our stewardship of the land.” Making vulnerability more apparent within these felted shapes and forms, viewers would be forced to confront the issues at hand and the importance of recognizing and caring about the myriad concerns at stake. The whimsical sculptures provide a compelling entry point into the important conversations provoked by the artist’s statement of intent.

|