Written by: Leah Moxley Teigrob, Gallery Assistant

Looking around my son’s preschool classroom, the walls are filled with the artwork of his classmates. Naturally, I scan the room for his name, and find among masterpieces, the crude depictions of my own family. Little legless blobs are noticeably less refined than the (slightly) more detailed work of his peers. Try as I might, the comparisons are inevitable. My heart sinks a little. Surely with an artist as a mother, my son shouldn’t be lagging behind in his drawing skills. One of my greatest joys as a parent is creating with my son. But my philosophy as an artist, mother and as a teacher is to leave room for creativity within the technical aspects of art making. I teach my students that there is no right way to paint a tree. I rarely correct kids when they start using materials in an unconventional way, even if it’s at the expense of those materials. When art is broken down into its most basic elements, you can find an infinite number of ways to paint a tree. My son is one of the most creative people I know. Maybe his blob family is a better reflection of his creativity than of his technical ability to draw. And aren’t ideas just as important as skill in the professional art world as well?

We’ve all overheard the comment “my kid could do that” in regards to what many would consider “high art,” and they may not be wrong, but that really isn’t the point, is it? I think of the work of Saskatchewan artist Ruth Cuthand. Her diverse practice includes both rudimentary acrylic paintings and incredibly detailed bead work.

On her website, Cuthand writes of the significance of her approach:

“In my early work, I adopted a consistently anti-aesthetic stance, refusing to be stereotyped by forcefully rejecting the authority of both Western high art and traditional Aboriginal art and design. In true anarchic style, however, I borrow freely from both when it suits my purposes.”

“How Much was Forgotten” by Ruth Cuthand. (Source)

Her beadwork also plays a role in the conversation of what constitute high art, one that arises often in the world of fine craft.

“Adopting the traditional craft of beading in my recent work was a way to continue to centre the Aboriginal woman in my art while addressing other issues of concern. Maintaining the anti-aesthetic principles on which my practice was founded, I have traded crudeness of style for materials and techniques that have long been denied status as serious art.”

“Don’t Breathe, Don’t Drink” by Ruth Cuthand (Source)

When it comes to fine craft, technical aspects are, of course, highly regarded. But part of the technical side of craft pertains to pushing the boundaries of the chosen medium. Much like a child in a preschool classroom, artists’ learning often arises from times of playful interaction with their materials. In my own practice, my best work is often a result of these times of play. The work is more about the free-flow of ideas than the tedious application of paint. When artists learn to trust their instincts instead of their instructions, we flourish. I won’t be taking my son’s crude family portraits off of the fridge any time soon.

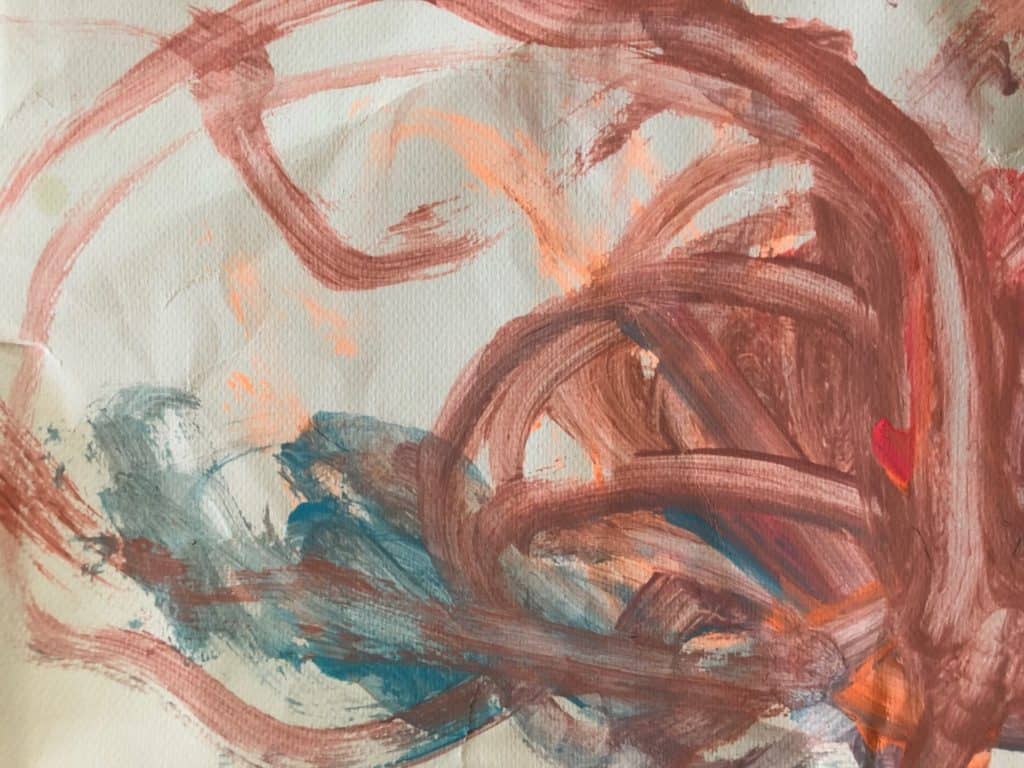

Untitled by Royal, Age 4